Adventures in Amateur Butchery

TW: meat from a wild animal; unusual application of free will; discussion of ethics

Oh, so you think you can have a 7 month break from food writing, then come and bombard your readers with an essay about how you just skinned and butchered a 14kg roe deer in your mate’s kitchen?

Yes. This is the point you can either unsubscribe (fair enough), or with any luck, pour yourself a glass of something interesting. It’s story time.

So.

On Sunday afternoon, me and a pal, Mika, purchased a deer from a man with a gun in East Kilbride. The deer had fur on it, but no head, guts or hooves. It cost £55. We strung it up from a pull-up bar in Mika’s kitchen doorway, using two climbing carabiners and some copper S-hooks designed for hanging pans. We then looped these through cuts made in the Achilles tendon on the hind legs where the deer had been hanging at the deer-man’s house for the last 36 hours. Putting some cardboard down to protect the floor, we then got to work peeling it.

Peeling a deer is more difficult than peeling a banana, but not by as much as you might think. Starting with a cut at the hind legs, and getting gravity to help you, you gently nip away with a filleting knife at the soft matrix of bubbly protein strands between the skin and the muscle. This substance is called fascia, which both lubricates and holds the skin (among other gubbins) in place. We worked on a side each, and after a slight mistake when I cut into my haunch while getting used to the knife, we managed to get the coat off in around half an hour; the work of moments, I presume, for a skilled butcher or gamekeeper, but Mika is a technology analyst for a battery company and I’m an outdoors writer, so we were mostly going slowly and enjoying the process.

Tanning (i.e turning the skin and fur into something usable, like a rug or some underwear) is a smelly, messy and time-consuming process. We both agreed that although the coat was gorgeous (the doe was wearing her thick winter fur, agouti patterned, with a dark brown line along the spine) it’d be too much of a faff to tan. Less than 24 hours later, we’d both gone away, done a bit of reading and reversed our thinking when we met again. Mika has the coat in his freezer, which he’ll process at a later date. It is too beautiful to waste.

Our deer, now naked, was beginning to look more like a piece of meat than an animal that had once skittered about destroying native woodland. We admired it for a moment, then hauled it into the bath to wash off the stray fur that had inevitably stuck all over it. The white of the bath against the deep red of the meat put the fact that is very much what you or I might look like underneath it all into stark relief. We carried on, nonetheless, washing away any fur, grass and debris using the shower head, before hanging our deer back up again to drip dry into a plastic box while we cleaned up around it, and then rolling the fur away into a bin bag for the freezer.

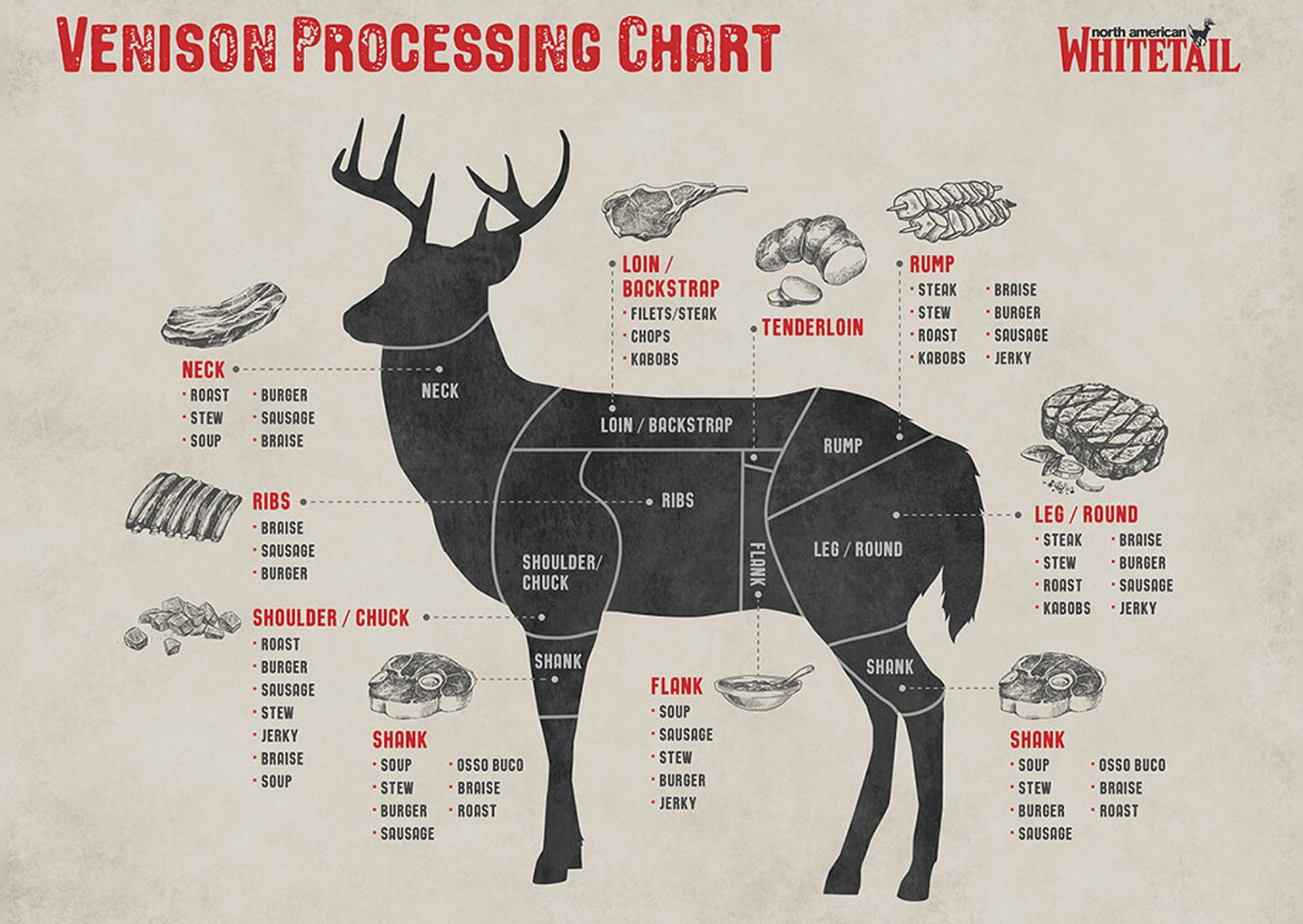

Chopping up a deer is slightly more difficult than peeling it. We started with taking the hind legs off, and for this we flopped it onto Mika’s kitchen table, making cuts along where the lowest rib met the hip to free the ball-and-socket joint, and liberate the haunches. These are stunning bits of meat: dark and thick with well-used muscle, the surfaces silver with sinew. Incidentally, we found this sort of butchery to be reasonably straightforward if you allow yourself to be led by the natural flow of the muscles and joints; things do come apart quite easily if you go along the right line of tendon. We decided that we’d macro-butcher the whole thing today, and then turn it into useable joints for cooking tomorrow, when we’d also decide how to split the trim and resulting bones.

We continued into the evening, removing the tenderloin (see above), front legs, and flanks. That left us with the ribs, still with the backstraps (fillet) attached, plus bits of trim sticking out, which we removed to put into a bowl to process later. At this point, we also removed all of the cavity fat (of which there was a surprising amount for a lean, wild animal, but we realised as a doe, she’d have been bulking up for the rutting season) and put that in a separate container to render later. Apparently deer tallow from lean, small deer isn’t all that tasty, making me ever-more grateful for domestic pigs, but we will attempt to make either candles or hot water crust pastry, depending on how it smells when rendering. The meatier trim has just enough fat on it to impart flavour, which we’ll grind with some pork fat to make either burgers or sausages, again at a later date.

In real time, this took us up to about 7.30pm, having started the process at about 4ish. It being a school night, we decided to put everything onto trays and put it into the fridge before cleaning up, and then enjoying the chef’s special - the tenderloin. This is the part of the animal that hasn’t much muscular work, so stays buttery soft. It’s where your fillet mignon comes from on a cow. Mika cooked both tenderloins in a ripping hot carbon steel pan, using goose fat, which has a blisteringly high smoke point. Seasoned with little more than salt and pepper, and cooked until a good vet could have got it up and running again, this was an absolute treat, and well worth the afternoon’s effort alone. We ate it with our hands, primally, and thanked the animal for its life.

Heading back to Mika’s place the next evening, we still had quite a lot of work to do. For the first time in around 4 years, I was feeling physically under the weather, so my concentration wasn’t great, but we needed to deal with separating the backstrap from the spine, cutting up the ribs, and jointing each limb into useable parts, as well as going through the trim and fat to find out what was going to be properly edible. Then we’d need to wrap, label, freeze and divvy. I also brought my hoover to Mika’s for a bit of an outing, and to suck up any fine stray hairs that the broom wouldn’t get.

Things went well. We deployed the bone saw (it’s just a B&Q hacksaw, lads) for separating the ribs and saddle, and then separated the shanks from both the shoulders and the legs. I slightly bungled getting the shank off the back leg, as I misjudged where the knee joint was in my brain-foggery and cut through some good muscle - but because this bit is all going to be stewed down, it didn’t matter too much. We then both took a haunch each and further divided the muscle into what would be silverside and topside in cow-terms.

Mika deboned his shoulder (as an aside, he really did dislocate his actual shoulder while climbing the other day) but I left mine bone-in, as by this point I was having a hallucination that I was butchering a deer in my pal’s kitchen. Getting the ribs off the spine was a two-person job, but easy once you got the saw blade going; they quickly peeled off one by one. Then, Mika performed some stellar knife-work getting those loins off the spine while I sorted through the trim and picked out 4 very un-tasty glands with the point of my knife.

Soon, we were done with knives and saws, and it was time to wrap, label and freeze. In the photo below, you can see what we ended up with. I’ll go through each bit, and what I’m planning to do with some of them, and then shout at you about what I personally took from this whole project. For the stuff that’s x1, we’ll cook together, then split the results.

Tenderloin x2: Yomp. Gone, sir. No idea where it went, sir.

Sirloin (Fillet) x2: Seared on all sides and served with jus and creamy mash, or having the bajesus wellingtonned out of it

Saddle x1: Possibly rolled like a porchetta with herbs and that (protected from high heat by a straightjacket of streaky bacon).

Topside x2: Roasty roast roast (or steaky steak steak)

Silverside x2: Tenderised in small chunklets for kebabs on the BBQ/slow cooked and put in a filthy medieval style game pie after stewing with juniper and bay

Ribs x2: slow barbecued/stewed down into ragu/osso bucco

Shoulder x2: I’d like to curry mine, low and slow with something spicy

Shanks x4: ragu/osso bucco/game pie. Much wine. Much braise.

Meaty trim x1: burgers and/or sausages with some extra pig and herbs and spices for good luck

Fat x1: make either into workable deer tallow for cooking with, or if smells funny, make into funny-smelling candle

Bones x many: stock response

Neck x1: as of yet undecided, but we’ll work it out. Apparently it’s super underrated, but it’s where our doe was shot, so we’ll have to be careful of the flavour here, as blood isn’t great to eat when it leaches into the meat.

Some Thoughts

It’s my belief that if you choose to eat meat, none of this should be shocking or gory to you. But to many people it is gory, because we’re so utterly disconnected from where our food comes from that we no longer acknowledge we’re eating actual animals that once had a heart, a central nervous system, lungs, guts, and gristle. One of my Hot Takes is that if you choose to eat meat, you should at least acknowledge where it has come from, and bear in mind the suffering the animal went through before it landed on your plate. I know and love at least two people who like meat, but not on the bone, and though I will always respect their wishes when I’m cooking for them, this is some spicy cognitive dissonance I do find hard to accept.

On that same vein, by putting all this time and effort into things, we really brought home the fact that our modern, western way of consuming meat - all boneless, skinless, hairless muscle, and wrapped in plastic packaging - is actually the disturbing thing here. Breaking down the carcass ourselves, in surprising contrast, felt respectful to the animal. There was no hacking away here; no violence or bloodlust or conquering. We did this quietly together, while listening to the radio, cutting away along the logical lines of a slightly gamey 3d jigsaw puzzle. There was practically zero waste created, and we’ll get so much food out of every single part of this creature - and that alone feels more natural, and indeed respectful, to me than buying an 8-pack of extra large boneless, skinless chicken breasts on any given weeknight.

If this were a newspaper article, I’d be obliged to mention here that venison is a hugely sustainable lean protein source, seeing as deer are considered pests in most parts of the UK, and there’s a real abundance of them, especially in Scotland. I’d also have to say something about the meat being good for you too, as it’s grass fed, high in omega 3s, full of vitamins and trace minerals, as well as being utterly delicious. But you’ve read this before. In fact, if you’ve got this far, you probably know this already.

More interesting to me as a person on the ground, I suppose, are the reasons why we don’t do more whole-animal butchery in the home. The cost of getting wild venison onto supermarket shelves is out of the question; there’s no way it can compete with the efficiency of grain fed, factory farmed chicken, pork beef or lamb. The venison you see in the supermarket is usually farmed, and usually imported from New Zealand. But why don’t more people buy whole, or even larger parts of an animal like a leg, to process at home?

This is not the mystery that people like me (food writers, chefs, middle class eccentrics) usually think it is. Mika and I spoke at length about the many privilege gaps involved in this endeavour. Yes, spending £27.50 on meat all in one go is out of reach for many, but at £4/kg, we’re talking far less than a joint of lamb or beef from the supermarket, and much less, even, than a joint of beef topside from a fancy butcher. Even a Deliveroo meal for two is usually touching the £30 mark, but the base price isn’t the main issue. The real cost of venison is in the time it takes to process.

Even after the guy shot, retrieved, gutted, and hung the animal for a day (at a cost of £55), two of us took a total of 7 hours to turn it into freezer-ready cuts, plus deal with the cleaning. At minimum wage, that’s £160 of labour, though a professional butcher will do it for around £60-70. The other facts of the matter are that neither of us have children, a second weekend job to make ends meet, chronic illnesses, or any other time-based obstacle in our way. Mika also has a large enough kitchen to do this in, not to mention the fact we did this in a Glasgow tenement flat in February, so the room stayed reasonably cool the whole time. And we had a makeshift way of hanging it directly on hand.

This leads me to the other privilege gap we both spotted: kitchen confidence. I know probably six people who are comfortable simply deboning chicken thighs, let alone dealing with jointing a whole chicken from the supermarket. Mika and I have both worked in commercial restaurant kitchens, breaking down chickens, fish, game birds, rabbits and hares into their component parts - admittedly not in the fur or feather, but the point is, we have a good understanding of how animals work, a selection of sharp knives and the confidence to use them. Mika has also done this before, in November with another pal, with two much smaller deer. And yet, we still found bits of this project reasonably challenging, with some amount of head-scratching and discussion needed, plus a bit of YouTubing, before making the right decision for the right cuts - some of which we still got a little wrong.

However, if you can get past all of these considerable obstacles, and find yourself a game dealer on a random Facebook page, I think this is something well worth investing the time and effort in. At minimum, it’s a sensory enrichment activity, which engages every part of the body, and gets you away from screens for a day or so. At maximum, however, it’s a respectful, sustainable, and bloody delicious way of consuming animal protein, which to us at least, gives a newfound appreciation for meat in general. We have plans to do this probably 2-3 times a year (we’ve both ended up with enough meat to last the rest of winter and spring, even if we were to make and eat something venison-based once or twice a week), and would like to involve more people next time, to see what we could do with a much larger red deer.

If you’ve reached this far, thank you. It means a lot. I know I’ll lose a lot of subscribers for this, but this is genuinely something I’m interested in, and for that I don’t mind a couple of folk ducking out if this isn’t what they expect. I’d also like to talk about my adventures in seafood foraging, namely scallop diving and mussel picking for the most part, so let me know if you’d read something like this. I might also think about documenting some venison recipes if that’s at all of interest, so let me know your thoughts in the comments.

Right, I’m off to make some ragu. Happy Wednesday, kids.

F xx

Excellent stuff as per! Pls keep us up to date on your new deer coat-coat business 😛

Should be in The Sunday Times Magazine. As should all your other stuff.